Originally published via the Untitled Magazine on February 15th, 2015.

Assuming you have seen the one-minute Jurassic World trailer that ran during the Super Bowl – and, let’s be honest, who hasn’t? – you know it opens on a clip featuring a five-ton Mosasaurus swallowing a great white shark as if it were a minnow. There is a message here, an overt signal that Universal seeks to release a summer blockbuster on such an epic scale it will dwarf the original Jaws. This is nonsense, of course, a claim that will only hold up in terms of box office, given inflation. Yet it speaks to something that exists within the DNA of the Jurassic franchise – specifically the involvement of Steven Spielberg, originally as a director (on the first two films), and ever since as a producer.

Jurassic Park may have come and gone had it not been for Steven Spielberg. It was Spielberg’s touch that gave that film its signature flair. Michael Crichton provided rich source material, sure, but only in the same manner Peter Benchley had previously. It was Spielberg who transformed what was on each page into a multidimensional thoroughfare. To that end, it’s safe to assume Spielberg approached both Jaws and Jurassic Park as being essentially about one thing – modern man being lured into a primordial kingdom, a reversal of the classic trope surrounding King Kong and, eventually, E.T.

The parallels between Jaws and Jurassic Park are revelatory – a study in the evolution of a director who’s mastered the occasional beats of rising action. The system with the barrels in Jaws serves the same purpose as the rippling water throughout Jurassic Park (the latter being a notion Spielberg concocted after noticing his rear-view mirror vibrate to Earth, Wind & Fire). The opening scenes of both films feature an innocent being eaten alive by an unseen predator. The tempo of John Williams’ score signals the proximity of danger. The structural symmetry is everywhere, from 40 minutes worth of development to holding off on major reveals (Both the T-Rex in Jurassic Park and the great white shark in Jaws appear for the first time around the one-hour-three-minute mark). In terms of central characters, you’ve got a man, a woman, two children, an academic and an eccentric. While Spielberg cuts out the torrid affair Hooper and Ellen Brody shared in Peter Benchley’s Jaws, he uses a similar – albeit more lighthearted – dynamic to heighten the tension between Jurassic’s Dr. Malcolm and Dr. Grant. Spielberg has famously shied away from documenting sex throughout his career. People rejoice, they hold hands, they might even kiss. But it will rarely go beyond that. Spielberg invariably enlists the point of view of his children, a perspective that’s proven critical to maintaining the majestic quality of his films.

The same can be said for Spielberg’s approach to man-eating leviathans. In both Jaws and Jurassic Park, Spielberg devotes considerable attention to the sense of awe these creatures inspire. Hooper “loves” sharks in the same way Dr. Grant and Dr. Sattler revere the awesome power of dinosaurs. Fear is an essential emotion, as well. Martin Brody “hates” the water in the same way Dr. Grant can’t stand dealing with children (and Spielberg’s Indiana Jones can’t stand dealing with snakes, for that matter). These characters are exposed to personal phobias repeatedly, providing a sense of development and comic relief. During the final minute of Jaws, Martin Brody says, “I used to hate the water”; during the final minute of Jurassic Park, Dr. Grant sits half-asleep, one child resting under either arm.

Money – specifically, Capitalism – represents an underlying omen. Mayor Vaughn doesn’t want to close the beaches for the same reason Jurassic’s Donald Gennaro (Esquire) becomes such an advocate for the park. The result is fatalistic. In Jurassic Park, Dr. Hammond spends most of the film championing his endeavor in the same way Mayor Vaughn champions the 4th of July. Consequently, it’s the risk of losing their own children – or grandchildren – that urges either man toward the light.

Spielberg has stated – on numerous occasions – that throughout the final hour of Jaws, he never wanted the horizon to feature anything but water. To see land would be to signal hope, and Spielberg wanted the audience to feel as if it was trapped. Isla Nubar (120 miles west of Costa Rica) in Jurassic Park maintains a similar purpose. Spielberg has effectively lowered his characters into a cauldron (John Carpenter is regarded as a master of this), forcing them to abandon any advantages involving home turf or man-made weaponry. That level of isolation allows for a takeover. Barriers get broken down, and what remains is a case of ingenuity versus power.

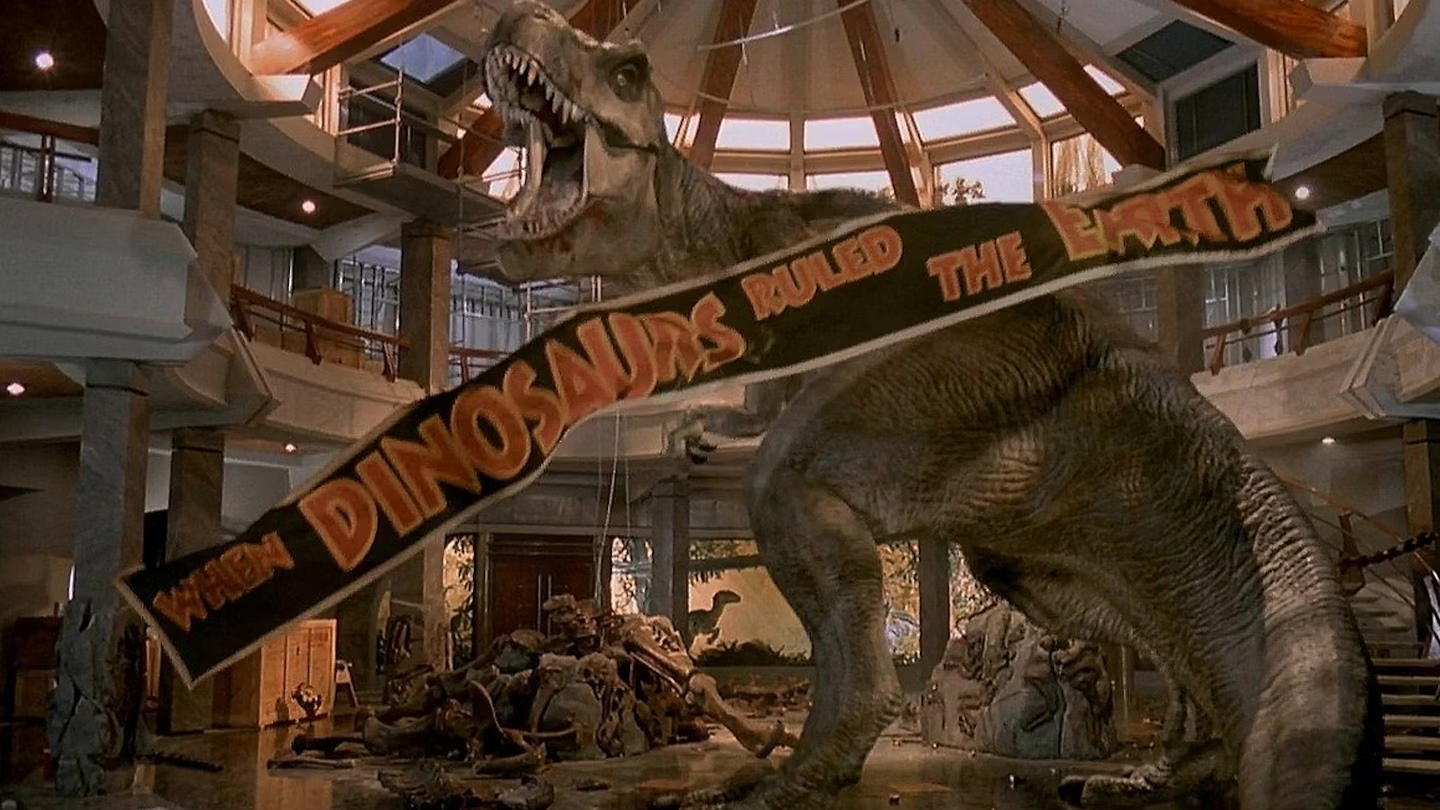

In Spielberg’s pitch for Jaws, he described the storyline as being “like Duel on the sea” (Duel was Spielberg’s first feature-length movie, a road-revenge thriller which Spielberg landed while directing television, most notably the pilot for Columbo). Spielberg would subsequently describe Jurassic Park as being “like Duel and Jaws combined.” This is critical, particularly as it relates to the ending of all three pictures. During the climax of Jaws, Brody blows the shark into oblivion. In the aftermath, Spielberg provides a dreamy, underwater sequence. Amidst the cloud of blood and guts and sea and pieces, one can see the dorsal fin appear, then disappear, accompanied by a roar. That roar is the same effect Spielberg uses when careening the deadly tanker off a cliff during the climax of Duel. It’s also the same sound utilized during the climax of Jurassic Park, as Spielberg’s T-Rex lets out a roar, a banner dropping slowly across the middle of the screen. Same moment. Same cadence. Same shot.

Same effect lifted from the original Godzilla, a creature howling madly over Tokyo Bay.

During the final moments of Jurassic and Jaws, Spielberg cuts to a wide shot of the ocean, birds flying at a distance. Our heroes are safe. A lot of our questions have been answered. Roll credits, one by one, against a backdrop of the sea.

Leave a Reply