By Bob Hill (Originally published via Crawdaddy Magazine in May of 2009.)

“I believe in his genius. He is an extraordinary writer, but I don’t think of him as an honorable person. He doesn’t necessarily do the right thing. But where is it written that this must be so in order to do great work in the world?”– Suze Rotolo, Notebook Entry, 1964

People grow old in different ways.

Some grow roots and others grow wings.

And some people, well, they just grow apart.

But pictures don’t lie. And it’s a helluva thing to look back on a picture years later and realize how much things have changed; that there’s no accounting for the many detours life takes along the way; that today is – in fact – a crooked highway, and there’s no way of knowing what’s waiting round each bend.

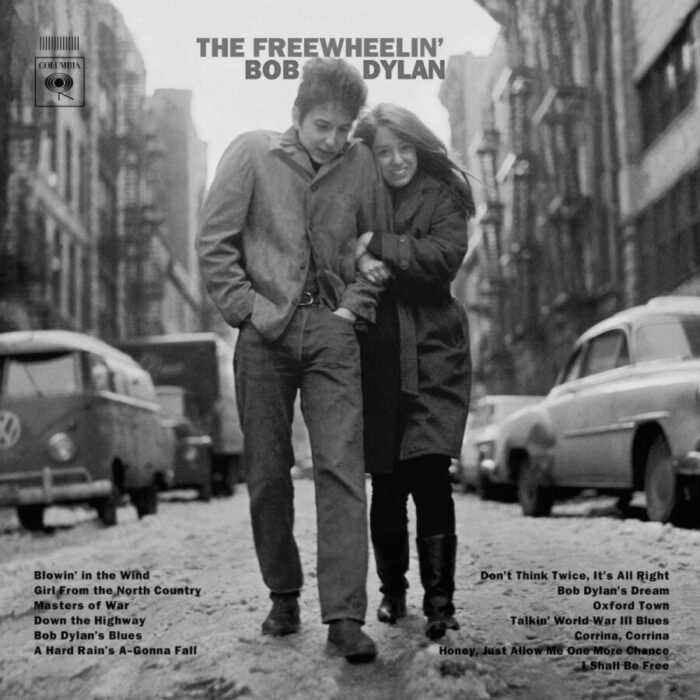

Just ask Suze Rotolo. Back in February of 1963 she appeared in a series of publicity photos with her then-boyfriend – an aspiring young folk singer named Bob Dylan. Three months later one of those photos ended up gracing the cover of Dylan’s second LP– an album that would help secure his reputation as Grand Poobah of the folk universe.

In the years since, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan cover photo has taken on an even greater significance – representing both the birth of a counterculture and the coronation of one of its most unique voices. In the picture, Dylan – a wiry, 21-year old kid in suede jacket and blue jeans – is linked arm-in-arm with Rotolo, an 18-year old girl he’d later refer to as “the fortuneteller of [his] soul.” The couple are walking north on Jones Street toward 4th. Both are leaning into one another for warmth, bracing themselves against the oncoming breeze.

They seem carefree. Confident. Two grains against the tide.

But those were different times. And in a sense, those were different people. Defiant. Idealistic. Unfettered by a world that grinds young dreams to dust. They embodied the spirit of a place and time that would change pop culture forever, rendered all the more poignant considering who (and what) Bob Dylan would eventually become.

But what if you were the person in that picture who didn’t go on to become Bob Dylan? What if you didn’t even go on to become Mrs. Bob Dylan? What if Bob Dylan slowly began to drift away, and you made a conscious decision to let him go? What if you were Suze Rotolo, four and a half decades removed, and you’d built an entirely separate life for yourself only a stone’s throw away from the West 4th Street apartment you and Dylan once called home? What if the world still identified you as “the other person” in that photograph?

What kind of lasting impact might that picture have on you?

“The girl on the cover became my identifier, but it was never my identity,” Rotolo tells Crawdaddy. “I fought against the image for years, probably a little too defensively (laughs). I saw it as a parallel existence, something that had to do with the past, but remained forever present because of Dylan’s lasting impact as a significant artist. Over time I learned to be more at ease with the holy fascination people have for him and realize that yes, I had lived through an amazing time, and I did so in my own right.”

Rotolo is the author of A Freewheelin’ Time: A Memoir of Greenwich Village in the Sixties. The book, which was published by Broadway (a subdivision of Random House) in May of 2008, provides a vivid, first-hand account of Greenwich Village during its heyday … before downtown railroad flats were converted into corporate condos, before the section south of Houston morphed into SoHo, before sky-high rent forced struggling young artists to migrate into Williamsburg.

It was the age of Ginsberg and Seeger and Dave Van Ronk; The Gaslight, Gerde’s and The Café Wha. It was a time when the Morningside Beats were making their way south, when the record industry was discovering new ways to mass-market folk. It was a time when musicians had to purchase a cabaret card before they were permitted to play in bars, when back-door bakery workers slipped fresh loaves of bread to their bohemian brethren in the wee hours of the morning. It was a time when the true measure of a poet was whether or not he “had something to say.”

It was a time when Greenwich Village went from section to scene, when young people descended upon the area in droves to be a part of what was happening. Suze Rotolo, a teenager from Queens, was one of them.

“The curiosity I had in my youth made the search inevitable,” Rotolo explains. “My arrival in Greenwich Village was like the world opening up. It was like finding life … [The book] is about a period that was special because of the cultural changes not only in music, but in all the arts, and maybe more importantly for the upheavals in society overall. Coming out of the 1950s lockdown on anything that deviated from the ‘norm,’ it seemed inevitable that things would change.”

Suze Rotolo first met Bob Dylan at a Manhattan folk festival in July of 1961. She was 17 years old. He was 20. And for the next three years – with the exception of a summer trip Suze took to Italy in 1962 – the couple were mostly inseparable.

In A Freewheelin’ Time Rotolo uses her relationship with Dylan as the focal point for everything else happening around them. And in that sense Bob Dylan plays a central role. But to her credit, Rotolo never exploits the relationship for her own purpose. And she doesn’t waste entire chapters obsessing over Dylan’s every whim. She describes him as someone who was immensely talented, and, as such, often difficult.

“I loved him and he loved me,” Suze writes. “But I had doubts about him, his honesty, and the way life would be.”

Moments like that strip away the Dylan mystique, painting him in more vulnerable terms than any other book has (with the possible exception of Chronicles). Particularly revealing are letters Dylan wrote while Suze was traveling abroad, letters in which he describes mundane things like missing her and how he wishes she hadn’t cut her hair.

“We were young and living our lives,” Rotolo explains. “There was no way I could think of it as ‘history in the making.’ Nor could I see Bob Dylan as an icon. He was my boyfriend and we were both in search of the poets…In those early years he was one of several performers who were better than average. What set him apart was something many thought was a negative, his voice – you either liked it or you didn’t. His ability to write songs that were good right off the bat – outshining others whose work was fine but more pedestrian – made it obvious he was headed somewhere.”

Dylan was headed somewhere, and he got there rather quickly. By the time the Newport Folk Festival hit in July of 1963, Dylan was already the undisputed belle of the ball. His newfound celebrity, and the overwhelming swell of publicity surrounding it, began to affect his relationship with Suze, most notably when rumors of an ongoing affair with Joan Baez began to surface.

Shortly after Newport, Suze began to distance herself from Dylan, first moving out of their West 4th Street apartment in August of ’63, and later parting ways with him for good on the street one night, Suze saying little more than “I have to go,” and Dylan offering nothing but a slight wave in return.

For a short while after, Dylan tried to rekindle their relationship, sometimes asking Suze to marry him, despite rampant reports of his other relationships. As the world outside began to demand more and more of Bob Dylan, it seemed a part of him still wanted to be that no-name kid, slushing down Jones Street with his girl – carefree, confident, two grains against the tide.

But neither one could go back. Too much had come to pass.

It was the beginning of a whole new era for Dylan, one of several reinventions that would keep him in the public eye for years to come. But it was the end of something as well. It was the end of the childlike innocence and blind ambition that brought Dylan and Rotolo to Greenwich Village in the first place. Bob Dylan was an international phenomenon now. And that meant there would always be expectations … expectations and classifications he’d spend the rest of his career railing against.

Bob Dylan went off to conquer the world and Suze Rotolo remained in the Village, becoming an advocate for civil rights both here and abroad. In the years that followed she would fall in love again, get married, raise a family, and build a career of her own.

“I live very much in the present,” Rotolo says. “And consequently, I tend to not see the past when I walk around the village today. What I am aware of, however, is the sad reality that most people can no longer afford to live in the East Village or West Village. In addition, stores that serve neighborhoods – shoe repair shops, cleaners, Laundromats, – have to close due to high commercial rents and that kills the essence of community, not to mention the soul of the city. The same stores selling the merchandise everywhere means there is no variety or character to a neighborhood. Eventually, Manhattan becomes homogenized.”

But “living in the present” doesn’t necessarily mean Rotolo forgets about that couple in the photograph, or the lasting significance of some of those early songs Dylan wrote about her (e.g., “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright,” “Tomorrow Is a Long Time,” “Boots of Spanish Leather,” to name a few).

“The old songs, from the early time in his life in which I participated, are so recognizable, so naked, that I cannot listen to them easily,” she writes. “They bring back everything. There is nothing mysterious or shrouded with hidden meaning for me. They are raw, intense and clear.”

Suze Rotolo is 64 years old now.

Bob Dylan is 67.

They both grew old in very different ways.

She grew roots and he grew wings.

And that young couple in the photograph? Well, they just grew apart.